By Tim Lambert

Haigh murdered people for money, then dissolved the bodies in acid. He was born on 24 July 1909 in Lincolnshire but his family moved to Yorkshire.

Haigh’s parents belonged to the Plymouth Brethren, a strict religious sect, although whether it had any bearing on his later behaviour is unknown. Haigh won a scholarship to attend Wakefield Grammar School, which meant he was a choir boy in Wakefield Cathedral.

After leaving school, Haigh did clerical jobs. He also married in 1934 but the marriage was short-lived. Haigh turned to fraud, but he was not very good at it. He kept getting caught.

His first prison sentence was in November 1934. He was released in December 1935. In 1936, he moved to London, hoping for a fresh start. For a time, he worked as a chauffeur for a young man named William McSwan. Haigh was convicted of fraud again in November 1937. He was released in August 1940. He then worked as a fire watcher, alerting the fire brigade when necessary.

However, in June 1941, he was sent to prison again. He was released in 1943.

It has been suggested that Haigh may have been affected by his experiences during the German bombing and that is what turned him to murder. Or maybe the third time he was sent to prison he was determined he was not going to get caught again.

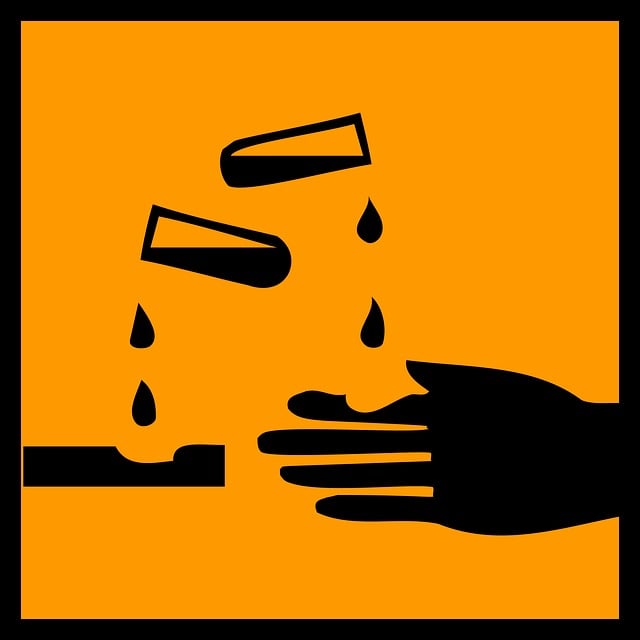

This time, while in prison, Haigh obtained acid from the prison workshop. He also obtained dead mice that prisoners had caught. He carried out experiments by dissolving dead mice in acid. It had obviously occurred to him that he could destroy a human body that way.

Haigh foolishly believed that he could not be convicted of murder if there was no body. He was wrong. English law does not require a body to prove murder.

Haigh often said that murder could not be proved without a corpus delicti. But he misunderstood the Latin phrase. It does not mean a human body; it means a body of evidence.

This time, after being released from prison, Haigh turned to murder. His first victim was William McSwan, who had employed him before. The two met, apparently by accident, and renewed their friendship.

On 6 September 1944, Haigh lured McSwan to a basement and then hit him over the head with an iron bar. He finished off McSwan and placed his body in an oil drum. He then filled it with acid. After two days, McSwan’s body had dissolved into sludge, which Haigh poured down a drain.

Haigh told William McSwan’s parents that their son had disappeared to avoid conscription. Haigh then persuaded them to employ him as a rent collector, which was a well-paid position. On 2 July 1945, he lured the father William McSwan’s father to a basement workshop where he killed him. His wife arrived about an hour later and Haigh killed her two. He had two oil drums prepared to dissolve the bodies.

Afterwards, Haigh faked their signatures. He sold the McSwan’s property and he persuaded people that they had emigrated to Australia. However, Haigh spent huge amounts on gambling and by 1948, he was starting to run out of money. His next two victims were Dr Archibald Henderson and his wife Rosalie.

On 13 February 1948, Haigh persuaded Dr Henderson to come to a workshop he rented in Crawley, Sussex by telling him he had an invention to show him. Haigh shot Dr Henderson with a revolver and placed him in an acid bath. Later, he lured Rosalie Henderson to his workshop. He shot her and dissolved her in acid, too. Once again, Haigh forged signatures, allowing him to sell their property. He managed to convince people that the Hendersons had gone to live in South Africa. But Haigh continued his lavish spending and before long, he was running short of money again.

His last victim was Olive Durand-Deacon. In 1949 Haigh was living at the Onslow Hotel in London. Mrs Durand-Deacon was a fellow guest.

She was a wealthy widow and she befriended Haigh. She had a scheme for manufacturing false fingernails and Haigh feigned interest. He invited her to come to his workshop in Crawley.

On 18 February 1949 Haigh gave her a lift there in his car. When she entered the workshop, he shot her in the back of the head.

Haigh placed the body in an acid bath. He then pawned Mrs Olive’s jewellery. He took her Persian lamb skin coat to a dry cleaner.

Haigh then drove back to London. Later, he went back to the workshop and poured out the dissolved body on the ground.

But Haigh was becoming careless. The body had not been completely destroyed, and traces of it remained on the ground.

Meanwhile, other residents of the hotel naturally noticed Olive was missing and became worried. A woman named Constance Lane told the police. They spoke to the other residents of the hotel and a policewoman, Alexandra Lambourne, was immediately suspicious of Haigh. She persuaded her superiors to see if Haigh had a criminal record. They then found out he had convictions for fraud.

They also discovered that he had a workshop in Crawley. They searched it and found a receipt for Olive’s Persian lamb coat from the dry cleaners. They also found a revolver that had recently been fired. They also discovered that Haigh had sold the dead woman’s jewellery.

Haigh realised the game was up and he confessed to the murder of Olive Durand-Deacon. He also told the police about the other murders he had committed. However, Haigh hoped he could avoid execution by pretending to be insane. He claimed to be a vampire and that he drank the blood of his victims.

The police searched the ground around the workshop in Crawley. Despite Haigh’s boast that he had completely destroyed the body of Olive Durand-Deacon, traces of her were found, including animal fat, which acid does not dissolve.

Olive had been suffering from gallstones and a layer of fat had surrounded them and protected them from the acid. There were also fragments of foot bones. (They probably survived because the body was not completely immersed in acid). Most telling of all, the police found a denture which a dentist identified as belonging to Olive.

Haigh went on trial for murder on 18 July 1949. He pleaded not guilty because of insanity. But the jury was most unlikely to accept his plea since he obviously killed for money.

Nevertheless, the defence called Dr Henry Yellowlees, who said that Haigh was a ‘paranoiac’.

However, the prosecution lawyer asked Yellowlees if Haigh knew he was doing something punishable by law. Yellowlees was forced to admit he did. The prosecution lawyer added, ‘Punishable by law and therefore wrong?’. Yellowlees had to say yes.

The jury found Haigh guilty of murder, and he was sentenced to death. John George Haigh was hanged on 10 August 1949.